As campaign announcements go, it was as splashy as could be: a page-one story in The New York Times of January 15, headlined “How Some Would Level the Playing Field: Free Harvard Degrees.” The article detailed a plan by five people to petition for slots on the annual ballot for Harvard’s Board of Overseers election under a common campaign theme, “Free Harvard, Fair Harvard.”

That the effort, helped by its catchy theme, would attract high-profile news coverage at the outset should be no surprise: its quarterback is Ron Unz ’83, who describes himself as a physicist by training and software developer by profession. (Unz created financial-services applications and founded and sold a company.) Of relevance in the current circumstances, he has published political and policy-advocacy media (The American Conservative and the Unz Review—an online articles archive and blog), and he is a veteran of California electoral politics (he sought the Republican gubernatorial nomination in 1994). Unz is especially known for engaging in that state’s high-stakes initiative process, where he was involved in campaigning against Proposition 187 (an anti-immigration measure; Updated January 28, 1:45 p.m.: Ron Unz notes that the proposition passed, but was subsequently ruled unconstitutional upon court review and was therefore overturned; the text previously indicated that the measure had been defeated by voters) and in a successful campaign to dismantle bilingual schooling (Proposition 227).

The issues raised in the shorthand language of the statements defining the petitioners’ campaign—which seeks to alter an expressed core value of the University, and its financial model—merit detailed discussion. This article accordingly reports on their objectives and the slate itself, and then directs readers to contextual information on the substantive matters.

The Platform and the Slate

Each winter (this year, on January 12), the Harvard Alumni Association (HAA) announces nominees for election as members of the Board of Overseers and as HAA directors, and notes further that “Candidates for Overseer may also be nominated by petition, that is, by obtaining a prescribed number [currently, 201] of signatures from eligible degree holders. The deadline for all petitions is Feb. 1.” The petition group is pursuing the required signatures now, with a platform, in two one-page statements, that proposes:

•“Harvard Should Be Fair,” and promises, “As Harvard Overseers we would demand far greater transparency in the admissions process, which today is opaque and therefore subject to hidden favoritism and abuse.”

Beyond this focus on “transparency,” the statement cites The Price of Admission, by Daniel Golden ’78 (reviewed here), as describing “the strong evidence of corrupt admissions practices at Harvard and other elite universities, with the children of the wealthy and the powerful regularly granted admission over the more able and higher-achieving children of ordinary American families. In some cases, millions of dollars may have been paid to purchase an admissions slot for an undeserving applicant.

“A nation that selects its elites by corrupt means will produce corrupt elites. These abuses must end.”

It then pivots to another point, drawing a substantive conclusion about admissions practices. It says, “…top officials at Harvard, Yale, Princeton and the other Ivy League schools today strongly deny the existence of ‘Asian quotas.’ But there exists powerful statistical evidence to the contrary.…Racial discrimination against Asian-American students has no place at Harvard University and must end.” [This claim is a subject of current litigation against Harvard; it is also an issue on which some members of the petition slate have expressed their conclusions—see discussion below.]

•“Harvard Should Be Free,” and promises, “As Harvard Overseers we would demand the immediate elimination of all tuition for undergraduates since the revenue generated is negligible compared to the investment income of the endowment.”

In support of this proposal, the statement continues, “Each year, the investment income the university receives from its private equity and securities holdings averages some twenty-five times larger than the net tuition revenue from its 6,600 undergraduate students. Under such circumstances, continuing to charge tuition of up to $180,000 for four years of college education is unconscionable.”

As a rationale, the statement asserts that, despite financial aid, “relatively few less affluent families even bother applying because they assume that a Harvard education is reserved only for the rich.” A Harvard decision to eliminate undergraduate tuition, the statement concludes, “would reach around the world, and soon nearly every family in America would be aware that a Harvard education was now free. Academically successful students from all walks of life would suddenly begin to consider the possibility of attending Harvard. Other very wealthy and elite colleges such Yale, Princeton, and Stanford would be forced to follow Harvard’s example and also abolition tuition. There would be considerable pressure on all our public colleges and universities to trim their bloated administrative costs and drastically cut their tuition.” [See the discussion below of endowment earnings, tuition and other unrestricted income, the sources of financial-aid funds, and other matters.]

The slate of petitioners who seek to be on the Overseers ballot includes:

- Ralph Nader, LL.B.’58, the consumer advocate, author, and founder of the Center for the Study of Responsive Law.

- Ron Unz

- Stephen Hsu, vice president for research and graduate studies, Michigan State University, where he is also a professor in the department of physics and astronomy. A Caltech graduate who earned his doctorate at Berkeley, he was a Junior Fellow at Harvard between 1991 and 1993. The biographical note put out by the petition campaign notes that Hsu has “written widely on public policy issues, including the indications of anti-Asian discrimination at elite universities.”

- Stuart Taylor Jr., J.D. ’77, journalist and author, former legal-affairs and Supreme Court reporter for The New York Times. He is affiliated with the Brookings Institution, where his biography states, “He has coauthored two critically acclaimed books. In 2012, Richard Sander ’78 and Taylor coauthored Mismatch: How Affirmative Action Hurts Students It's Intended to Help, and Why Universities Won't Admit It. In 2007, Taylor and KC Johnson coauthored Until Proven Innocent: Political Correctness and the Shameful Injustices of the Duke Lacrosse Rape Fraud. They are planning a new book on the supposed ‘epidemic’ of campus rape.” The Federalist Society lists him as an “expert” (meaning only that he has spoken at or participated in events).

- Lee C. Cheng ’93, chief legal officer of Newegg Inc., and a co-founder of the Asian American Legal Foundation (Updated February 2, 8:10 a.m.: the website, previously reported as inactive, has been restored after a software update). The petition biographical note observes that he has “been actively involved for over two decades in issues related to anti-Asian discrimination at secondary schools, colleges, and universities.”

In a January 19 post, “Meritocracy: Will Harvard Become Free and Fair?” (at his Unz Review), Unz again focused on “increasing the transparency of today’s opaque and abuse-ridden admissions process” and eliminating College tuition. In campaign mode, he writes,

Will our campaign succeed? Maybe, maybe not. Based on all indications so far, I have little doubt that if our names do appear on the annual Overseer ballot and our position statements are mailed out to the 320,000 Harvard alumni, we will win a resounding victory throughout the Harvard community, and soon thereafter Mighty Harvard will agree to forego 4% of its annual investment income and henceforth become tuition-free, while also starting to shift its admissions process from abusive total opacity to some degree of reasonable transparency.

Conflicting Worldviews on Admissions

•University Policy

Harvard has long emphasized the diversity of its student body as a core institutional value: one of the principal ways to expose students to difference, choice, and intellectual stimulation as a fundamental part of their education not only within the classroom, but also in extracurricular activities and in the residential setting. (The institutional amicus filings submitted to the U.S. Supreme Court during recent rounds of litigation over the use of race in admissions at public universities, discussed below, indicate that selective universities and colleges generally share this view.) Harvard’s leaders during the past half-century have gone to unusual lengths to articulate the importance of this value. A summary of some of the important statements follows.

In 1995, President Neil L. Rudenstine delivered “Diversity and Learning,” a report to the Overseers, devoted entirely to the history and importance of the idea of diversity as fundamental to learning, broadly and at Harvard. In a conversation about the essay, Rudenstine emphasized that diversity underpins effective learning and promotes the conditions for democracy in a heterogeneous society. (Read Harvard Magazine’s excerpt here.) He prefaced his report with two resonant quotes from prominent predecessors. He cited Charles William Eliot to the effect that

Democracy does not seek equality through the discouragement or obliteration of individual diversities. It does not aim at a general average of gifts and powers in humanity. The prairie is not its social ideal. Its conception of social and political equality does not involve a dead level of human gifts, powers, or attainments. On the contrary, democratic society enjoys and actively promotes an immense diversity among its members….

He also cited James Bryant Conant’s observation that “A college would be a dreary place if it were composed of only one type of individual. A liberal education is possible, it seems to me, only in an atmosphere of tolerance engendered by the presence of many [individuals] with many minds.”

Rudenstine observed that “student diversity has, for more than a century, been valued for its capacity to contribute powerfully to the process of learning and to the creation of an effective educational environment. It has also been seen as vital to the education of citizens—and the development of leaders—in heterogeneous democratic societies such as our own,” and so has shaped Harvard’s admissions policies.

Those policies, he noted, reflect the reality that “When such a large proportion of applicants are barely distinguishable on statistical grounds, SAT scores and GPAs are clearly of only limited value. Admissions processes therefore must remain essentially human. They must depend on informed judgment rather than numerical indices. And they will be subject to all the inevitable pressures and possible misconceptions that any exceptionally competitive selection process involves.”

Effective admissions policies, committed to excellence, required Harvard to “continue to admit students as individuals, based on their merits: on what they have achieved academically, and what they seem to promise to achieve; on their character, and their energy and curiosity and determination; on their willingness to engage in discussion and debate, as well as their willingness to entertain the idea that tolerance, understanding, and mutual respect are goals worthy of persons who have been truly educated.” Evaluation of applicants gives “appropriate consideration” to grades, test scores, and class rank” but those metrics are “viewed in the context of each applicant’s full set of capabilities, qualities, and potential for future growth and effectiveness.” Further, Harvard also “will seek out—in all corners of the nation, and indeed the world—a diversity of talented and promising students.”

Indeed, “any definition of qualifications or merit that does not give considerable weight to a wide range of human qualities and capacities will not serve the goal of fairness to individual candidates (quite apart from groups) in admissions. Nor will it serve the fundamental purposes of education. The more narrow and numerical the definition of qualifications, the more likely we are to pass over (or discount) applicants—of many different kinds—who possess exceptional talents, attributes, and evidence of promise that are not well measured by standardized tests.”

Looking beyond undergraduate education, Rudenstine made an argument about society, and about graduates’ future directions (and economic prospects) generally:

[I]f we want a society in which our physicians, teachers, architects, public servants, and other professionals possess a developed sense of vocation and calling; if we want them to be able to gain some genuine understanding of the variety of human beings with whom they will work, and whom they will serve; if we want them to think imaginatively and to act effectively in relation to the needs and values of their communities, then we shall have to take diversity into account as one of many significant factors in graduate and professional school admissions and education.

A few years later, Princeton president emeritus William G. Bowen, LL.D. ’73, and Harvard president emeritus Derek Bok collaborated on The Shape of the River: Long-Term Consequences of Considering Race in College and University Admissions, drawn from data on the life experiences of students at 28 selective colleges and universities (excluding Harvard). In this magazine’s review, Daniel Steiner (who had been vice president and general counsel in the Bok administration) noted the two presidents’ roles in “taking race into account as a ‘plus factor’—in their own and other institutions.” Their book gave “two clear reasons for supporting race consciousness in admissions to selective schools”: preparing “qualified minority students for the many opportunities they will have to contribute to a society that is still trying to solve its racial problems within a population that will soon be one-third black and Hispanic”; and providing “a racially diverse environment that can help prepare all students to live and work in our increasingly multiracial society.” Steiner found the authors’ evidence supportive of affirmative action in admissions on both counts.

He also found persuasive the authors’ argument that proxies for race, such as low socioeconomic status, would not have a similar benefit—on sheer arithmetic grounds alone (given the large number of lower-income but academically qualified white students compared to similar black students). He also cited their finding that “The data do not support those who believe that blacks with lower scores than their classmates at the most selective schools would fit better at less selective schools” (the “mismatch” theory; see discussion below).

During the Supreme Court review of admissions policies at the University of Michigan and its law school, in the 2002-2003 academic year (see below), President Lawrence H. Summers emphasized the “vital educational benefits for all students” of bringing them together from different backgrounds, and the benefit to society of educating graduates who will, accordingly, be better prepared to “serve as leaders in a multiracial society.” Such admissions policies, he noted, “carefully consider each applicant as a whole individual, not just as a product of grades or test scores,” and so are more appropriate than externally imposed “blunter” policies or standards that purport to be oblivious to ethnicity or race. When the ruling in Grutter v. Bollinger upheld the law school’s consideration of race in admissions, Summers cited the “paramount significance for our community” of the court’s embrace of “the core principles that have long informed Harvard’s approach to admissions.”

At the beginning of the current academic year, last September, President Drew Faust used the occasion of her Morning Prayers remarks (read the text) to highlight diversity:

I often remark that for many if not most of those arriving at Harvard for the first time, this is the most varied community in which they have ever lived—perhaps ever will live. People of different races, religions, ethnicities, nationalities, political views, gender identities, sexual orientations. We celebrate these differences as an integral part of everyone’s education—whether for a first year student in the College or an aspiring M.D. or M.B.A. or LL.M.—or for a member of the faculty or staff, who themselves are always learners, too.

She then pointed to litigation (see below) seeking to overturn the University’s admissions procedures in support of that diversity, and announced sharp opposition to the claims being made: “Harvard confronts a lawsuit that touches on its most fundamental values, a suit that challenges our admissions processes and our commitment to a widely diverse student body. Our vigorous defense of our procedures and of the kind of educational experience they are intended to create will cause us to speak frequently and forcefully about the importance of diversity in the months to come.”

Finally, in December, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences heard a report from the Committee to Study the Importance of Student Body Diversity (chaired by Harvard College dean Rakesh Khurana), and will be asked, in formal legislation, to endorse it as a “statement of the values embraced by the Faculty” during a meeting this spring. It cites Rudenstine’s 1995 report and Faust’s Morning Prayers remarks, and finds that “The exposure to innovative ideas and novel ways of thinking that is at the heart of Harvard’s liberal arts and sciences education is deepened immeasurably by close contact with people whose lives and experiences animate those ideas. It is not enough, Harvard has long recognized, to read about or be taught the opinions of others on a given subject.”

To that end, the report continues,

Our students arrive at Harvard with their identities partially formed, shaped by racial, ethnic, social, economic, geographic, and other cultural factors, a sense of self both internally realized and externally recognized. Four years later, our students are welcomed by the President of the University to embrace an additional identity, that of membership in “the community of educated men and women.” A critical aspect of our transformational goal is to encourage this second and complementary identity, one inclusive of but not bounded by race or ethnicity, one that is sensitive to and understanding of the rich and diverse range of others’ identities, one that opens empathic windows to imagining how other identities might feel. This we aspire to do by creating contexts where students interact with “other,” with those having different realized and recognized identities, and by providing academic, residential, and extra-curricular opportunities for these interactions.

If the only contact students had with others’ lived experiences was on the page or on the screen, it would be far too easy to take short cuts in the exercise of empathy, to keep a safe distance from the ideas, and the people, that might make one uncomfortable. By putting those people and those ideas on the other side of the seminar table—and in one’s own dormitory rooms and dining halls—we ensure that our students truly engage with other people’s experiences and points of view, that they truly develop their powers of empathy. As President Conant explained, “[t]olerance, honesty, intellectual integrity, courage, [and] friendliness are virtues not to be learned out of a printed volume but from the book of experience.”

The role played by racial diversity in particular in the development of this capacity for empathy cannot be overstated.

•Admissions issues before the Supreme Court

Whether and under what conditions public universities may constitutionally consider race and ethnicity in admissions has been the subject of recurrent litigation. Harvard and other private institutions with selective admissions policies have been interested parties, filing amicus briefs, in these cases (both because of their diversity goals, and because they receive public research funding). Harvard has become particularly involved because its admissions policy, described in one such filing—including consideration of applicants’ race or ethnicity as part of a holistic review of individual applicants’ candidacy—was cited with approval in the Supreme Court’s ruling in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978), the landmark case that has since shaped institutions’ practices and subsequent litigation.

When the issue reached the Court again, in 2002-2003, Harvard filed an amicus brief supporting the Bakke standard (see President Summers’s comments above). The Court’s ruling in Grutter v. Bollinger (2003) upheld consideration of race in admissions to the University of Michigan’s law school; Justice Sandra Day O’Connor cited Justice Lewis F. Powell’s Bakke opinion extensively.

The issues have arisen again in two further rounds of Supreme Court deliberations: the 2012 litigation in Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, which was sent down to a lower court for further review; and the review and new arguments in Fisher this past December.

Concerning the 2012 case (extensive background here), President Faust said, “A diverse student body is fundamental to the educational experience at Harvard. Bringing together students from different backgrounds and walks of life challenges students to think in different ways about themselves, their beliefs, and the world into which they will graduate.” Robert W. Iuliano, senior vice president and general counsel, said that the amicus brief Harvard filed with peer institutions sought to underscore “why we think student-body diversity both improves the quality of education on campus and creates successful citizens in a world that is diverse and pluralistic.” The institutions emphasized the “profound importance of assembling a diverse student body—including racial diversity—for their educational missions.” Diversity, they argued, “encourages students to question their own assumptions, to test received truths, and to appreciate the spectacular complexity of the modern world. This larger understanding prepares Amici’s graduates to be active and engaged citizens wrestling with the pressing challenges of the day, to pursue innovation in every field of discovery, and to expand humanity’s learning and accomplishment.”

Because race continues to play a role in society, the brief continued, some students are inevitably affected or even shaped by it. Given that, the brief argued, “If an applicant thinks his or her race or ethnicity is relevant to a holistic evaluation—which would hardly be surprising given that race remains a salient social factor—it is difficult to see how a university could blind itself to that factor while also gaining insight into each applicant and building a class that is more than the sum of its parts…In view of that reality…it would be extraordinary to conclude at this time that race is the single characteristic that universities may not consider in composing a student body that is diverse and excellent in many dimensions, not just academically.”

When the case returned to the Supreme Court last fall, Harvard again filed an amicus brief. In summarizing the University case both for diversity in its student body and the admissions process used to admit those students, the brief noted:

This Court has long affirmed that universities may conclude, based on their academic judgment, that establishing and maintaining a diverse student body is essential to their educational mission and that the pursuit of such diversity is a compelling interest. Petitioner does not directly challenge that holding here, with good reason. It is more apparent now than ever that maintaining a diverse student body is essential to Harvard’s goals of providing its students with the most robust educational experience possible on campus and preparing its graduates to thrive in a complex and stunningly diverse nation and world. These goals, moreover, are not held by Harvard alone, but are shared by many other universities that, like Harvard, have seen through decades of experience the transformative importance of student body diversity on the educational process. This Court should therefore reaffirm its longstanding deference to universities’ academic judgment that diversity serves vital educational goals.

The Court should also reaffirm its previous decisions recognizing the constitutionality of holistic admissions processes that consider each applicant as an individual and as a whole. Harvard developed such policies long before they were embraced by Justice Powell in Bakke and reaffirmed by this Court in Grutter. In Harvard’s judgment, based on its decades of experience with holistic admissions, these admissions policies best enable the university to admit an exceptional class of students that is diverse across many different dimensions, including race and ethnicity. Admissions processes that treat students in a flexible, nonmechanical manner and that permit applicants to choose how to present themselves respect the dignity and autonomy of each applicant, while also permitting Harvard to admit exceptional classes each year. Compelling Harvard to replace its time-tested holistic admissions policies with the mechanistic race-neutral alternatives that petitioner suggests would fundamentally compromise Harvard’s ability to admit classes that are academically excellent, broadly diverse, extraordinarily talented, and filled with the potential to succeed and thrive after graduation.

Thus, the University argues for a diverse student body along multiple dimensions— including, it is no secret, applicants who have distinguished skills as athletes, artists, and organizers and leaders of groups of peers (as well as academically qualified legacies). Further, the College regularly reports the expressed academic interests of admitted candidates, suggesting its interest in a student body whose fields of study span the areas (from arts and humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences to engineering and applied sciences) in which it has determined it is important to offer teaching faculty and to support faculty research. And in support of those interests, it advocates an admissions process that relies onall sorts of evidence of the sort Rudenstine described: academic metrics—like test scores and transcripts, evaluation of the rigor of high-school courses—and recommendations, essays, presentations in interviews, examples of academic research or artistic performance, etc.

•The petitioners’ views

As the recurrent litigation indicates, the issues surrounding admissions remain controversial. Some litigants argue that any consideration of race is impermissible. Others claim that students admitted to selective institutions under any sort of preference are likely to be disadvantaged by the experience (the mismatch argument). Some Asian Americans have argued that preferences granted to one group in pursuit of diverse student bodies constitute discrimination against Asian-American applicants; much of the evidence advanced focuses on quantitative metrics of academic qualification (grades and standardized test scores), and deemphasizes or dismisses as illegitimate other evaluative criteria. Several of these arguments arise in the work of the slate of petitioners seeking to become Overseer candidates, under the “Harvard Should Be Fair” claims about admissions transparency, admissions abuses, and racial discrimination (see above). Ron Unz, in particular, has written extensively on these subjects.

His January 19 post refers to his more substantial writing on the subject and carries a link after the post to “The Myth of American Meritocracy,” published in late 2012 by his magazine, The American Conservative—the source for his subsequent online roundtables on admissions and finances in The New York Times, and opinion columns elsewhere.

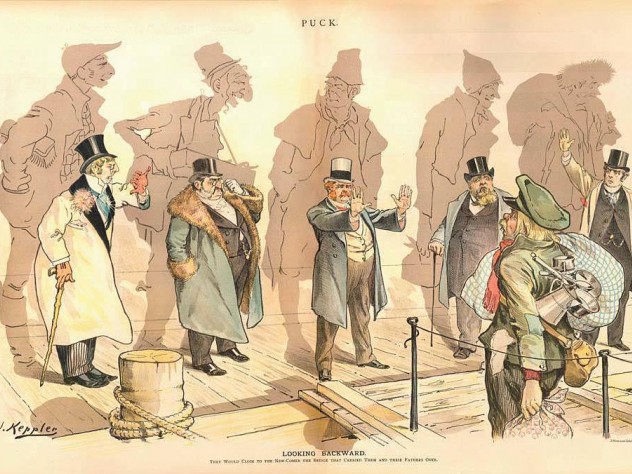

Unz’s background in quantitative disciplines and theoretical physics very much comes through in his approach and analysis. In part, the “Myth” essay is a review of the argument in Golden’s book and other books on admissions, documenting past infamies such as the “Jewish quota” on admissions in the early twentieth century. In part, it is a statistical analysis of the family names of National Merit Scholarship (NMS) semifinalists (which are based on students’ Preliminary SAT, or PSAT, scores), “a reasonable proxy for the high-ability college-age population,” and of winners of elite national mathematics and science competitions, also seen as proxies for academic achievement and capacity.

Unz then compares his findings from those samples to the ethnic composition of elite universities’ enrollments. Relative to the quantitative metrics he uses as proxies for achievement and ability, he finds systematic, wholesale under-enrollment of Asian Americans. By the same measures, he finds that “Jewish academic achievement has apparently plummeted in recent decades,” resulting in a “massive apparent bias in favor of far less-qualified Jewish applicants” being enrolled, coinciding with “an equally massive ethnic skew at the topmost administrative ranks of the universities in question.” He speculates that the apparent over-enrollment of Jewish students at elite institutions perhaps reflects the school leaders’ unconscious, implicit biases.

Citing other works, Unz concludes that “it seems likely that some of these obvious admissions biases we have noticed may be related to the poor human quality and weak academic credentials of many of the university employees making these momentous decisions.” Thus,

I suspect that the combined effect of these separate pressures, rather than any planned or intentional bias, is the primary cause of the striking enrollment statistics that we have examined above. In effect, somewhat dim and over-worked admissions officers, generally possessing weak quantitative skills, have been tasked by their academic superiors and media monitors with the twin ideological goals of enrolling Jews and enrolling non-whites, with any major failures risking harsh charges of either “anti-Semitism” or “racism.” But by inescapable logic maximizing the number of Jews and non-whites implies minimizing the number of non-Jewish whites.

He concludes that in battles over admissions policies at elite, selective institutions,

Conservatives have denounced “affirmative action” policies which emphasize race over academic merit, and thereby lead to the enrollment of lesser qualified blacks and Hispanics over their more qualified white and Asian competitors; they argue that our elite institutions should be color-blind and race-neutral. Meanwhile, liberals have countered that the student body of these institutions should “look like America,” at least approximately, and that ethnic and racial diversity intrinsically provide important educational benefits, at least if all admitted students are reasonably qualified and able to do the work.

My own position has always been strongly in the former camp, supporting meritocracy over diversity in elite admissions. But based on the detailed evidence I have discussed above, it appears that both these ideological values have gradually been overwhelmed and replaced by the influence of corruption and ethnic favoritism, thereby selecting future American elites which are not meritocratic nor diverse, neither being drawn from our most able students nor reasonably reflecting the general American population.

He considers a pure-diversity admissions scheme (“require our elite universities to bring their student bodies into rough conformity with the overall college-age population, ethnicity by ethnicity”), which would be “extremely difficult to implement in practice” and would “foster clear absurdities, with wealthy Anglo-Saxons from Greenwich, Conn., being propelled into Yale because they fill the ‘quota’ created on the backs of the impoverished Anglo-Saxons of Appalachia or Mississippi.”

On the other hand, he states that “strictest objective meritocracy,” with students “automatically” selected “in academic rank-order, based on high school grades and performance on standardized exams such as the SAT,” risks introducing a high-stakes testing atmosphere like those that plague admissions to national universities in Japan, Korea, and the People’s Republic of China. That approach would also “heavily favor those students enrolled at our finest secondary schools, whose families could afford the best private tutors and cram-courses, and with parents willing to push them to expend the last ounce of their personal effort in endless, constant studying. These crucial factors, along with innate ability, are hardly distributed evenly among America’s highly diverse population of over 300 million, whether along geographical, socio-economic, or ethnic lines, and the result would probably be an extremely unbalanced enrollment within the ranks of our top universities, perhaps one even more unbalanced than that of today.”

His solution is “two rings” of admissions. For an entering Harvard College class, the inner ring, of perhaps 300 academic and intellectual stars, would be carefully selected on purely objective academic and intellectual meritocratic criteria (“representing just the top 2 percent of America’s NMS semifinalists”) from among the most promising candidates. Everyone else, the outer ring in each class (1,300 undergraduates per year), could be selected randomly—the proverbial flip of the coin—from among all the applicants who seem able to handle rigorous undergraduate studies.

(Note that this randomization would eliminate admissions officers’ review of applicants’ files for “outer-ring” candidates, consistent with Unz’s criticisms of those officers’ qualifications. It would also do away with efforts to achieve various kinds of diversity in constructing an undergraduate class as a whole, leaving the result to the composition of the applicant pool and randomization. He is also explicit in giving greater weight to what might be considered purely academic or intellectual achievement than to outstanding performance in other realms. As he put it, “Under such a system, Harvard might no longer boast of having America’s top lacrosse player or a Carnegie Hall violinist….But the class would be filled with the sort of reasonably talented and reasonably serious athletes, musicians, and activists drawn as a cross-section from the tens of thousands of qualified applicants, thereby providing a far more normal and healthier range of students.”)

In “Racial Quotas, Harvard, and the Legacy of Bakke” (National Review, February 5, 2013), Unz wrote about admissions policies then under review as the Supreme Court weighed its first ruling in Fisher v. University of Texas. Citing the 1978 Bakke ruling, he concluded:

Suppose we accept the overwhelming statistical evidence that the admissions offices of Harvard and other Ivy League schools have been quietly following an illegal Asian-American quota system for at least the last couple of decades. During this same period, presidents of these institutions have publicly touted their “non-quota” approach to racial admissions problems, while their top lawyers have filed important amicus briefs making similar legal claims, most recently in the 2012 Fisher case. But if none of these individuals ever noticed that illegal quota activity was occurring under their very noses, how can their opinions carry much weight before either the public or the high court?

If the “Harvard Holistic Model” has actually amounted to racial quotas in disguise, then a central pillar of the modern legal foundation of affirmative action in college admissions going back to Bakke may have been based on fraud. Perhaps the justices of the Supreme Court should take these facts into consideration as they formulate their current ruling in the Fisher case.

(Jeff Neal, the University’s chief spokesman, issued this statement pertaining to these matters:

Harvard College’s admissions policies are essential to the pedagogical objectives that underlie its educational mission and are fully compliant with the law.

When a similar claim—that Harvard College discriminated against Asian American applicants—was investigated by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights, federal officials determined that the College’s approach to admissions was fully compliant with federal law.

In fact, within its well-rounded admissions process, and as part of its effort to build a diverse class, Harvard College has demonstrated a strong record of recruiting and admitting Asian American students. For instance, the percentage of admitted Asian-American students admitted to Harvard College has increased from 17.6 percent to 21 percent over the past decade. Asian Americans today make up less than 6 percent of the American population.)

Other members of the petitioners’ slate have attacked the use of race in admissions decisions head-on. In a February 2012 online New York Times“Room for Debate,” Stephen Hsu, then at the University of Oregon, wrote:

Race-based preference produces a population of students whose average intellectual strength varies strongly according to race. Surely this is opposite to the meritocratic ideal and highly corrosive to the atmosphere on campus. Furthermore, the evidence is strong that students of weaker ability who are admitted via preference do not close the gap during college. For these reasons, the Supreme Court would be wise to end the practice of race-based preference in college admissions.

In a Bloomberg View published the same month (“What Harvard Owes Its Top Asian-American Applicants”), he wrote, “It is terribly corrosive to use race as an important factor in what are superficially (disingenuously?) described as meritocratic evaluations.”

Hsu has detailed his criticisms of Harvard in posts on his blog, for example: “…a simple calculation makes it obvious that the top 2000 or so high school seniors (including international students, who would eagerly attend Harvard if given the opportunity), ranked by brainpower alone, would be much stronger intellectually than the typical student admitted to Harvard today.”.

Lee C. Cheng appears as a counsel with the Asian American Legal Foundation on amicus briefs to the Supreme Court in both 2012 and 2015 in the Fisher cases, opposing the admissions practices of the University of Texas. In the 2012 brief, the argument concluded that “this Court should expeditiously reject racial diversity as a compelling interest and overrule its holding in Grutter.” The 2015 amicus brief, for the Court’s rehearing of Fisher, cites Unz’s 2012 report, among many other sources; it concludes that “the Court should find the UT admission program to be unconstitutional. This court should also revisit its holding in Grutter, to make clear that outside of a constitutionally permissible remedy to prior discrimination, race may not be considered in college admissions.”

(A separate matter is the litigation to which President Faust referred in her Morning Prayers remarks. The Project on Fair Representation, founded to “Support litigation that challenges racial and ethnic classifications and preferences,” represents Abigail Fisher in the University of Texas cases. It has also filed suits against Harvard and the University of North Carolina, both aiming at overturning Bakke. The claim against Harvard, brought under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 —therefore applicable to a private entity—asserts that “the proper judicial response” is “the outright prohibition of racial preferences in university admissions—period.” The claim focuses on alleged discrimination against Asian Americans, using the kind of data Unz has presented—and in fact citing his 2012 Myth piece explicitly. In responding to the complaint, the University has argued that until the Supreme Court rules in Fisher, determining the admissions issues raised there, it would be premature to proceed with discovery in the Harvard case. For now, the action is largely in abeyance.)

In an amicus brief in the 2012 Fisher case, Stuart Taylor and Richard Sander (of UCLA School of Law)—speaking for themselves in advance of publication of their Mismatch book on affirmative action—argued that:

- racial preferences were not effective;

- the Court should order institutions to make much greater disclosure (to applicants and in the aggregate) about their “current and planned use of racial preferences in admissions and the academic consequences thereof”—the transparency theme;

- the Court should order schools to disclose their “timetable for phasing out racial preferences by 2028” as envisioned in Grutter; and

- schools “that wish to take race into account [should] demonstrate (through disclosure) that the weight assigned to race in admissions decisions does not exceed the weight given to socioeconomic factors.”

(Taylor and Sander’s mismatch argument about the suitability of various kinds of institutions for students of varying academic abilities figured prominently in the Court’s oral arguments on the new round of the Fisher case, last December, when Justice Antonin Scalia, LL.B. ’60, appeared to refer to it, asking whether black students might be better served by going to “a school where they do well” rather than to a more elite, selective one that uses racial preferences in its admissions evaluations; read a New York Times account here.)

•Admissions criteria

The College Board, academic analysts generally, and Harvard admissions officers have indicated that SAT scores are predictive of students’ possible performance during their first undergraduate year, but not beyond. In fact, dueling studies, including one just released, question whether the SAT even predicts one year of performance reliably. Presumably, evidence from PSAT tests, taken earlier in high school, has no stronger predictive value. And as noted, access to tutoring may have some influence on scores.

Harvard College’s admissions announcements have regularly noted that thousands more applicants than can be admitted to an entering class are at the top tier of various single-point measurements. For the class of 2010, for example, nearly 2,600 applicants achieved a perfect (800) score on the SAT’s verbal test, and 2,700 achieved that score on the math section: more than 10 percent of that year’s applicant cohort. (In recent years, the College has published SAT scores by the number of applicants exceeding 700 on the verbal, math, and writing sections: more than 10,000 in each category each year.) And applicants to the class of 2018 included 3,400 high-school valedictorians: one-tenth of those in the applicant pool, more than double the number of those eventually enrolled in the class—and down from the 3,800 valedictorians in the pool of applicants for the class of 2016.

Unz took note of the latter phenomenon in his 2012 essay, observing that “Harvard could obviously fill its entire class with high-scoring valedictorians or National Merit Scholars but chooses not to do so. In 2003, Harvard rejected well over half of all applicants with perfect SAT scores, up from rejecting a quarter a few years earlier….” (He did not address the possibility that the increase in rejections reflected rising applicant numbers.)

During an extended telephone conversation from Palo Alto on January 22, Unz was asked what he thought ideal admissions criteria and procedures might be, in pursuit of his preferred meritocratic process.

Unz responded that his ideal criteria were “not entirely clear,” and reiterated his call for “greater transparency” about admissions. The Golden book, he said, was a “horrifying” view of admissions, and his own analyses of admissions “shocked” him, making him “much, much more supportive of a much more meritocratic admissions” system focused on academic ability and performance. Evaluations based on determining “has this person been involved in that project, [and] all these essays,” in contrast, presented “tremendous opportunities for outright corruption.” In search of a system focused on his preferred academic criteria, he had suggested his “thought experiment” about randomizing much of the decisionmaking about most of the applicant pool.

Such a system, he said, was “several steps” beyond what the petitioners are presenting as their platform as potential Overseer candidates. Given his focus on academic merit, he said, consistent with his 2012 essay, “I have doubts about Harvard selecting top athletes or musicians or artists,” whose presence might tend to crowd out peers who sought a spot on the football team or in the orchestra. An outstanding musician, he said, might go to Juilliard instead of the College. But such issues, he noted, are “awfully complicated” and “not what we’re running on.”

Abolishing Undergraduate Tuition?

In arguing that “Harvard Should be Free,” the petitioners note that undergraduate tuition revenue “is negligible compared to the investment income of the endowment”—typically, “some twenty-five times larger than the net tuition revenue” from College students.

The argument then proceeds to several other steps:

- First, given endowment earnings, charging tuition is “unconscionable.”

- Second, Harvard financial aid is insufficient or ineffective because “relatively few less affluent families even bother applying because they assume that a Harvard education is reserved only for the rich” (given the nominal price of tuition, room, and board); announcing a tuition-free plan would broaden the applicant pool as students “from all walks of life would suddenly begin to consider the possibility of attending Harvard.”

- Third, other elite, selective institutions “would be forced to follow Harvard’s example,” and public institutions would face pressure “to trim their bloated administrative costs and drastically cut their tuition.”

During a populist U.S. presidential campaign, that platform rolls up many resonant issues, including: college affordability generally; public concern about the cost of higher education; and public institutions’ increased term bills since the 2007-2008 financial crash and ensuing recession (when hard-pressed states reduced budgets for higher education, absolutely and per capita, and institutions responded by increasing their term bills).

It also speaks, indirectly, to the line of reasoning that socioeconomic status might, or ought to, supplant other kinds of preferences or plus-factors in admissions decisions—a case made in many arguments against using any racial or ethnic considerations in assembling a diverse student body. Unz, who raised the tuition issue in a sidebar to his 2012 "Myth" essay, spelled out his thinking about tuition and admissions in a 2015 New York Times online forum. He wrote:

Harvard claims to provide generous assistance, heavily discounting its nominal list price for many students from middle class or impoverished backgrounds. But the intrusive financial disclosures required by Harvard's financial aid bureaucracy may be a source of confusion or shame to many working-class households. I also wonder how many lower-income families unfamiliar with our elite college system see such huge costs and automatically assume that Harvard is only open to the very rich.…

The announcement of a free Harvard education would capture the world's imagination and draw a vastly broader and more diverse applicant pool, including many high-ability students who had previously limited their aim to their local state college.

•Levels of aid

Responding to the New York Times article on the petitioners’ campaign, Robert D. Reischauer, former Senior Fellow and a member of the Corporation through the period when undergraduate financial aid was increased significantly (beginning in 2004 and subsequently extended and enhanced), wrote to the newspaper. His letter, headlined “Free Tuition at Harvard? It’s Already Affordable,” noted:

Over the last decade Harvard has awarded undergraduates $1.4 billion in financial aid. Aid is based on need and consists entirely of grants. No student is required to take out loans.

Over all, nearly 60 percent of students receive grant aid, and on average their families pay $12,000 a year for tuition, room, board and fees combined. For nearly 20 percent of students—those from families with the most modest incomes—the expected family contribution is zero.

Separately, University spokesman Jeff Neal issued this statement:

Through Harvard College’s generous, need-based, loan-free financial aid program, every undergraduate has the opportunity to graduate debt-free, regardless of their financial circumstances.…

One in five undergraduate families pays nothing for tuition, room, and board because their annual income is $65,000 or less. At higher income levels, families pay between zero and 10 percent of their annual income for tuition, room, and board (for example, $12,000 for a family with $120,000 a year in income and typical assets).…

Today, a Harvard College education costs the same or less than a state school for 90 percent of American families, based on their income and because of Harvard’s financial aid.

In conversation, Unz said that families simply were unaware of the extent of aid, and that aid formulas were complex, involving calculations of family means and contributions, student work, possible loans, and so on. In contrast, “Free tuition is very, very simple.”

Asked whether he had any concerns about providing a free ride to the 30 percent to 40 percent of undergraduate families who now pay full term bills, Unz said, “I don’t think it makes much difference one way or another.” (The Harvard Crimson, citing “an unnecessary subsidy to students whose families…can afford to pay for college,” on January 26 editorialized, “Don’t Eradicate Tuition.”)

•Research-university finances

If the petitioners’ slate qualifies for the ballot and its argument about tuition proceeds toward fuller discussion, several interesting issues will arise from the operation of the endowment, distributions from it, and the flow of restricted and unrestricted funds within the University and its components.

At a gross level, the petitioners’ exhibit compares investment income to tuition. But investment income is not the same as the funds distributed from the endowment for Harvard’s operating budget; the University, like most endowed institutions, distributes a portion of endowment value each year (plus or minus 5 percent) in an effort both to smooth the effects of volatile investment results (so the University can adhere to a budget) and to protect its future value and support for future operations, in perpetuity. In fiscal year 2015, when endowment returns net of investing expenses were a relatively low 5.8 percent, the investment returns totaled about $2 billion, and endowment distributions totaled about $1.6 billion. (Before financial-aid expenses, student income from undergraduates—tuition, room, and activity fees collected by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences [FAS], plus dining and health revenues collected by the University—was about $392 million.)

At a slightly finer degree of resolution, the FAS owned $15.4 billion of the endowment, which was valued at $37.6 billion last June 30: about 41 percent. Approximately $2.5 billion (slightly less than 7 percent) of the endowment is presidential funds—the income from some of which may be directed to FAS and the College. But the remaining majority of endowment assets is owned by other schools or units, and presumably the income distributed from them is largely or completely unavailable to pay for undergraduate tuition (though undergraduates benefit from funds that may support those schools’ faculty members who teach freshman seminars and General Education courses, as well as graduate teaching fellows, libraries, and so on).

Refining still further, many endowment gifts come with restrictions on their use. (Neal issued a statement indicating that 70 percent of endowed funds carry restrictions.) FAS has aggressively sought endowment support for financial aid, both undergraduate and graduate. But (based on data from FAS’s managerial financial report, which is not in conformance with the GAAP accounting for Harvard’s annual financial statement), it remains the case that in the fiscal year ended last June 30, for FAS’s core operations—the College, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and the faculty proper:

- Unrestricted income totaled $592 million, of which $410 million (gross) or $320 million (net of undergraduate and graduate financial-aid spending) came from tuition and room and activity fees.

- After unrestricted financial-aid spending, those net tuition and fees of $320 million were more than half of FAS’s total unrestricted revenues, and nearly one-third of total revenues ($974 million) for the core operations.

- A major use of unrestricted funds ($90 million) was for financial aid (benefiting both College and graduate students). More than half this sum was for undergraduate aid.

- Total spending for undergraduate financial aid in the year was $170 million—suggesting that unrestricted funding (of which tuition and fees is the principal source) accounted for about one-third of the total College aid budget.

Thus, a decision to eliminate undergraduate tuition (holding aside room, board, and all associated student fees, for which FAS of course also incurs aid expenses) would imply reducing FAS’s core income by somewhat more than 10 percent, and its unrestricted core incomeby more than one-sixth. FAS’s unrestricted funds in total pay for more than half of salaries and benefits, most of building operations, virtually all of the debt service on FAS’s borrowings, and some of the start-up costs for new professors’ laboratories and research, libraries, and so on. (This comes at a time when the FAS is operating at a budget deficit.)

Research universities all have such internal transfers—and all undergraduates accordingly benefit from faculty members, libraries, and so on for which they do not fully pay. To the extent that some students can and do pay the full term bill, they are in effect agreeing to help subsidize the operations (teaching and, importantly, research), facilities, and assets—and some of the fellow students among whom they choose to study.

A decision to eliminate College tuition thus goes to the financial model of the FAS and the larger University.

•Attracting applicants

Unz, who has recent relevant experience, may well be right that were Harvard to announce it was making the College tuition-free, the story, as he put it, “would be on the front page of half the world’s newspapers.” It would be, he said, “a gigantic earthquake in U.S. higher education.”

Beyond the obvious problem of costs, higher-education scholars have also examined the extent to which factors such as the lack of mentors, inadequate high-school counseling, and other conditions surrounding potential applicants deter them from pursuing admission to a selective institution in which they might thrive, and from which they might receive significant financial aid. Asked about those constraints, Unz focused again on tuition per se: “I think it’s a bigger factor than most people think.” Elite families in New York, Boston, and Palo Alto are aware of college costs and aid programs, he said, but “I would bet that the overwhelming majority of people on the nonelite side of things are very skeptical about Harvard being affordable.”

As noted, the cost of eliminating tuition would seem to be about $100 million in annual unrestricted income—an expensive way to gain extensive news coverage that would boost the College admissions office’s already extensive outreach to potential applicants (mailings, visits, students and alumni, etc.) Although there have been discussions in Congress about forcing well-endowed private institutions to boost their spending on undergraduate financial aid, it is far from clear that financially strained public institutions welcome either heightened pressure to cut their own costs further or intensified competition from richer, endowed colleges and universities—which already offer aid packages that undercut in-state tuition, thus luring away the most qualified local applicants.

In Prospect

In a recent e-mail communication, Unz indicated that “matters are now looking pretty good on the signature side.” He had previously said that petitions had been express-shipped to several hundred alumni. As noted, each petitioner must present 201 eligible signatures by February 1.

This magazine has been advised that if sufficient signatures are verified to place some or all of the petitioners on the ballot, it will be notified as soon as practicable after February 15, so the full slate of nominees can be published. (The magazine’s March-April issue goes to the printer earlier in February; if additional candidates qualify by petition, the full slate will be noted in the online version of the March-April issue, which goes live toward the end of February, and then in the printed May-June issue.) Ballots are mailed April 1 and results are announced during the annual meeting of the Harvard Alumni Association on the afternoon of Commencement, May 26.

Candidate statements are circumscribed: a couple of hundred words. In past petition campaigns for Overseer, the petitioners have invested in more extensive outreach, and Unz has previously demonstrated his skill in organizing such efforts. In conversation, he said, a “campaign itself is a very useful means to focus attention on these issues,” and noted that “a crucial thing in any initiative campaign is media attention.” But he obviously would like to achieve more.

If there is a vigorous campaign, University staff members, who ultimately report to the governing boards—the Overseers and the Corporation—would be expected to refrain from involvement. The boards themselves are not under that constraint. As Harvard’s presidents for the past half-century have made clear, the University regards the diversity of the student body, and the process the College uses to admit students, as fundamental to its educational enterprise. The University has engaged vigorously in voicing its views in the Fisher cases, and has retained the same counsel to represent it in the pending complaint directed at Harvard: Seth P. Waxman ’73—a former U.S. solicitor general, and former president of the Board of Overseers. President Faust’s Morning Prayers remarks reemphasize that commitment.

And if the petitioners’ slate is nominated and elected? There would be 25 other members, plus the 13 Corporation Fellows (including the president) with whom the newly elevated Overseers would have to engage in debate about admissions and Harvard’s basic financial model.